Egypt’s government has cancelled its planned official commemoration of the January 25th Revolution in 2011. The reason: the seven-day mourning period announced after the death of King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia on Friday. The timing of the Saudi monarch’s demise can be seen as an ironic favor for the pro-revolutionary camp, since it thwarts President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s efforts to appropriate the legacy of the revolution to his own ends. In life, of course, King Abdullah was actually a great proponent of the pre-revolutionary status quo, and systematically sought to undermine the Arab Spring movements. He gave a home to Tunisia’s deposed dictator, actively supported Bahrain’s crackdown on its own protest movement, and bankrolled General Sisi’s brutal and reactionary administration from its first day.

The Sisi administration has always had a conflicted relationship to January 25th. Sisi wouldn’t be where is today without the Tahrir Square uprising that overthrew Mubarak four years ago, and he claims much of his legitimacy from the revolution — despite the fact that new Egyptian president has restored quasi-military rule and many aspects of Mubarak-era autocracy. His alleged loyalty to the revolution is a crucial plank in his argument against those who see his accession to power as a coup. While Jan. 25, 2011, is hailed by many around the world as the end of a despot, Sisi’s supporters see June 30, 2013 — the day the general overthrew the government of Mohamed Morsi — as its logical extension.

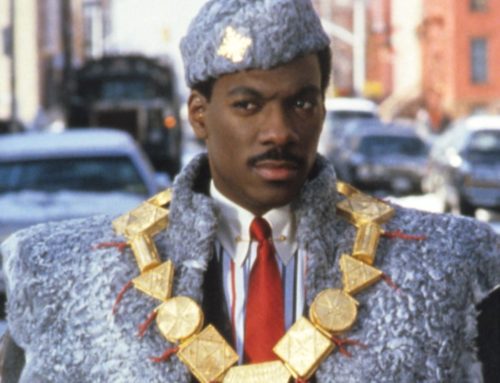

This week the Egyptian state chose to celebrate the occasion in the way it knows best: A few hours before Jan. 25, the police shot and killed Shaimaa Al-Sabbagh, a socialist political activist who also happens to be the mother of a 5-year-old son. Sabbagh was part of a small march to place flowers on a memorial to the 2011 revolution in Tahrir Square. Security forces brutally dispersed the march even though it had been authorized by the proper authorities. Some have already dubbed Sabbagh “the Rose Martyr.” Her violent death was documented on video, and the images are as heartbreakingas you’d expect them to be. (The photo above shows a plainclothes security officer detaining a demonstrator yesterday at gunpoint.)

The police killed another young woman the day before — 17-year-old Sondos Reda Abu Bakr, shot in the head and neck with birdshot as the police dispersed a pro-Muslim Brotherhood protest in Alexandria. The frail teenager was demanding justice for her aunt, who had been killed two months earlier. Activists quickly took to the web to post photos of Sabbagh and Abu Bakr under the title “Sisi, the Killer of Women.”

Today, limited protests around Cairo and other main cities have also been met with lethal violence. By the early afternoon, the ministry of health hadannounced 18 dead today, most clashes between protesters and uniformed or plain-clothed security forces. The actual toll is likely to be higher; 150 protesters were arrested.

The entire cycle seems absurd — and all too reminiscent of the period before 2011, when small protests, met with extreme violence, were the order of the day. The key difference today, however, is the attitude of the general public. Though once silently supportive, perhaps uttering a silent prayer for the protection of the brave protesters, large segments of the Egyptian population are now either indifferent to the protesters and their fate — or, more frighteningly, loudly approving of their killing. A cursory look at public statements by pro-regime media (some of whom were recently revealed to be receiving direct orders from the government on what to say and write) in the immediate aftermath of Shaimaa Al-Sabbagh’s killing reveals a now-habitual pattern of denying state responsibility, usually by blaming some other culprit (either the Muslim Brotherhood or a fictional “third party”), then giving way to vitriolic celebration of the victims’ deaths, based on crude insinuations of criminal or subversive activity. The fact that this sort of state-sponsored defamation raises no eyebrows, and that no one dares to demand any sort of investigation (which would never happen anyway), is the new reality that we have to confront.

The dilemma facing pro-democracy Egyptians is that they feel a moral imperative to take a stand against state repression, officially sanctioned killing sprees, and a tragicomically unjust legal system. Emboldened by the recent memory of 2011, when mass protests led to change, the first impulse of the activists is to take to the streets, to chant, to make demands. At the same time, however, these killings and the corresponding culture of official impunity make it all too clear that the act of objecting is a potentially suicidal one, punishable by death or egregious prison sentences and police torture. The current limited protests are a manifestation of this cognitive dissonance, in which, for some, adherence to principles overrides the instinct for self-preservation. However one chooses to resolve this conflict, the courage of the protesters cannot be overstated.

The most heart-wrenching part of Shaimaa Al-Sabbagh’s killing may be her last moments, which were recorded on video. As her husband carries her bleeding body through the narrow streets of downtown Cairo, frantically asking for help, for a ride to the hospital, for someone to hail a taxi for him, he is met with shrugs. People sitting at the café he walks past don’t get up to help. No car offers a ride. Finally he sets her down on a chair, helpless and tired, and caresses her hair.

The tragic metaphor is impossible to miss. The apathetic majority stares blankly at the dying embodiment of the ideals held by so many just a few years ago. Bystanders fail to lift a finger in assistance, preferring to watch life seep from her body rather than risk the chance that their tea might get cold.

For the past four years, the Egyptian masses have been so limited by short-term, myopic thinking that they’re willing to do anything — perhaps even to sacrifice their own future — for the sake of that warm cup of tea. Entrusting their destiny to a despot may serve to maintain this illusive “stability” that is constantly being promised, but in the long term, few of them, aside from members of the regime’s inner circle, will emerge victorious. Eventually almost everyone will suffer from systemic injustice, or at the very least from the mismanagement of state affairs by an unaccountable regime.

For all these reasons, this January 25th, despite its heartening associations, is hardly a day to celebrate. As political scientist Timothy Kaldas wrote, “Egypt should be in a state of mourning, but not for a foreign king who beheads his people. It should be in a state of mourning for Shaimaa Al-Sabbagh, and the thousands like her who were murdered during their struggle for freedom.”

Happy January 25th. For what it’s worth.

Originally published on Foreign Policy Magazine: Transitions.